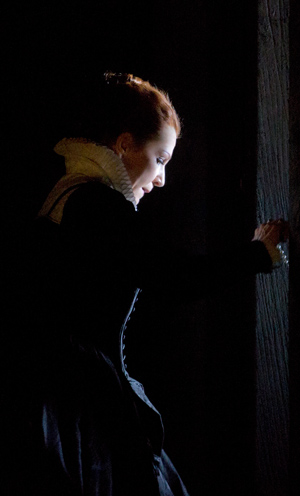

Maria Stuarda, Metropolitan Opera

“The production stars the great American mezzo-soprano JoyceDiDonato in the title role, a part that has been sung by sopranos and mezzo-sopranos. Ms. DiDonato’s performance will be pointed to as a model of singing in which all components of the art form — technique, sound, color, nuance, diction — come together in service to expression and eloquence.

Ms. DiDonato is simply magnificent, singing with plush richness and aching beauty. At a few moments, from the collective sounds of the subdued chorus and orchestra, a pianissimo high note, almost inaudible, emerged from Ms. DiDonato’s voice, slowly blooming in sound and throbbing richness. I left the house not just moved but renewed, and ready to celebrate the arrival of a new year.” ~ Anthony Tomassini The New York Times January 2013

“Most important, [DiDonato] treats the complex bel-canto flights as emotional expressions, never merely as bravura filigree. This is an exquisitely proportioned, remarkably sensitive performance.” ~ Martin Bernheimer Financial Times January 2013

“SEARING AND INSPIRED: DiDONATO TRIUMPHS

DiDonato, now at the peak of vocal and interpretive resplendence, grasps the key element of early nineteenth-century Italian opera: the word and not, as so many ignorant commentators have claimed, “mere” vocal fireworks. To be sure, she served up virtuosity aplenty on Tuesday evening, whether in the form of a slender, glistening, exquisitely tapered thread of sound in her final prayers or in the giddy, defiant volley of roulades that she unfurled to thunder Mary’s contempt for Elizabeth. In the 1800s, though, the line between spoken and sung theatre was weakly drawn. Actors intoned and declaimed; Malibran and other singers drove audiences into a frenzy with their vehement and razor-sharp recitation; and composers, including Verdi, Wagner, and the giants on whose shoulders they stood, Donizetti among them, prized artists who dug into their words while also delivering the vocal goods.

It is a mark of DiDonato’s greatness that, with a voice of modest size that she never abuses or inflates, she repeatedly drew thunderstruck ovations from a Met audience that so often mistakes decibels for excellence. The most memorable aspect of her performance for this writer was her unfailingly meaningful engagement with her role: her nostalgic caress for “France,” the lost, gracious kingdom that Mary recalls; the scalding, haunted tones she summoned when facing the ghosts of her past in Act II; and the acceptance and grace that infused her soaring melismas when Mary resolved to wash away Elizabeth’s remorse with her own blood. Even in our era of wondrous prowess in the music of Handel, Rossini, and others, DiDonato reigns supreme.

DiDonato carries all before her, and for her sublime, commanding performance and for Maria Stuarda’s long-overdue arrival at the Met we must be very grateful indeed.” ~ Marion Lignana Rosenberg The Classical Review January 2013

Ms. DiDonato brought a luminous, meditative loveliness to Mary’s nostalgic opening aria, in which she thinks back to her home in France; the soft, floating trills were magical. But you could also see the effort required by her attempt at submission to Elizabeth, and her pride resurfaced with ferocious intensity. Equally fascinating was the confession scene, with the turbulence of her guilt giving way to an angelic serenity. Even her final aria—on her way to the block, she forgives Elizabeth—became a demonstration of Mary’s victory. She may be losing her head, but as her voice soared above the chorus she had the moral upper hand.” ~ Heidi Waleson The Wall Street Journal January 2013

“From the moment she makes her entrance in the second scene, singing of her joy in strolling outside her prison in Fotheringay Castle, DiDonato rivets attention. She imbues every syllable with a concentrated eloquence that makes her compact voice seem larger than it is. She displays seemingly effortless command of coloratura embellishments throughout a wide vocal range. And she is equally impressive in fiery outbursts and in hushed, long-held phrases – like the ones she spun out as she sang through the chorus in the final scene.” ~ Mike Silverman Associated Press January 2013

“DiDonato’s crowning achievement came in the sublime prayer to God in which she is joined by the entire chorus. During this moment, Mary is asked to sing two extensive high notes over the chorus. DiDonato demonstrated the true meaning of Bel Canto on both notes as she started them softly and slowly built them into a full flowered crescendos that were gut-wrenching in there execution. By the end of the opera, one should feel Mary’s growing strength and the idea that her death would finally be liberation from her suffering. DiDonato’s performance not only created this catharsis, but revealed the inner beauties of an often overlooked score.” ~ David Salazar Latinos Post January 2013

“Donizetti’s score is unusual in that either role — Mary or Elizabeth — can be cast for a soprano or a mezzo. Some of the great bel canto sopranos of the last few decades, including […] Sutherland and Sills, have undertaken the role of Mary. DiDonato makes a strong case that it rightfully belongs to the mezzo.” ~ Wilborn Hampton Huffington Post January 2013